Special Summer Issue | August 2025

Featuring the winners of our summer contests and new writing from our Spring 2025 Creative Writing cohort.

Welcome to our special summer 2025 issue of Writers’ Hour Magazine!

This issue gathers together the work that has flourished across our community in recent months. Over the summer, we invited writers to respond to the prompts A Summer Memory, Conversation with a Place, I Have to Tell You, In the Orchard, and Ekphrasis. From hundreds of submissions, we are pleased to present the top three winners from each contest, whose pieces reflect the range and vitality of our community’s creative practice.

Alongside these winning entries, we are proud to showcase new writing from the Spring 2025 cohort of the London Writers’ Salon Introduction to Creative Writing Course. Their work, developed over weeks of play and conversation, extends the spirit of experiment and devotion

Taken together, these pages mark a season of attention, imagination, and craft. We are honored to publish them here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. A Summer Memory

A Dark Green by Nica Máre

Dead-Man's Float by Patricia McTiernan

Which one of you geniuses by Matthijs Schut

II. Conversation With a Place

Scattering ashes in the company of dragonflies and deer by Kay Kroger

To Barnaul, with Love by Mauri Johnson

An Imaginary Conversation by Rathin Bhattacharjee

III. I Have to Tell You

An Unexpected Honesty by Dorit d'Scarlett

At his feet by Farhad Desai

The Aura of Our House by Claudia Excaret Santos

IV. In the Orchard

three applegarths by Philippa Francis

Trace by Sua Im

A Worthwhile Crop by Sandra Stratan

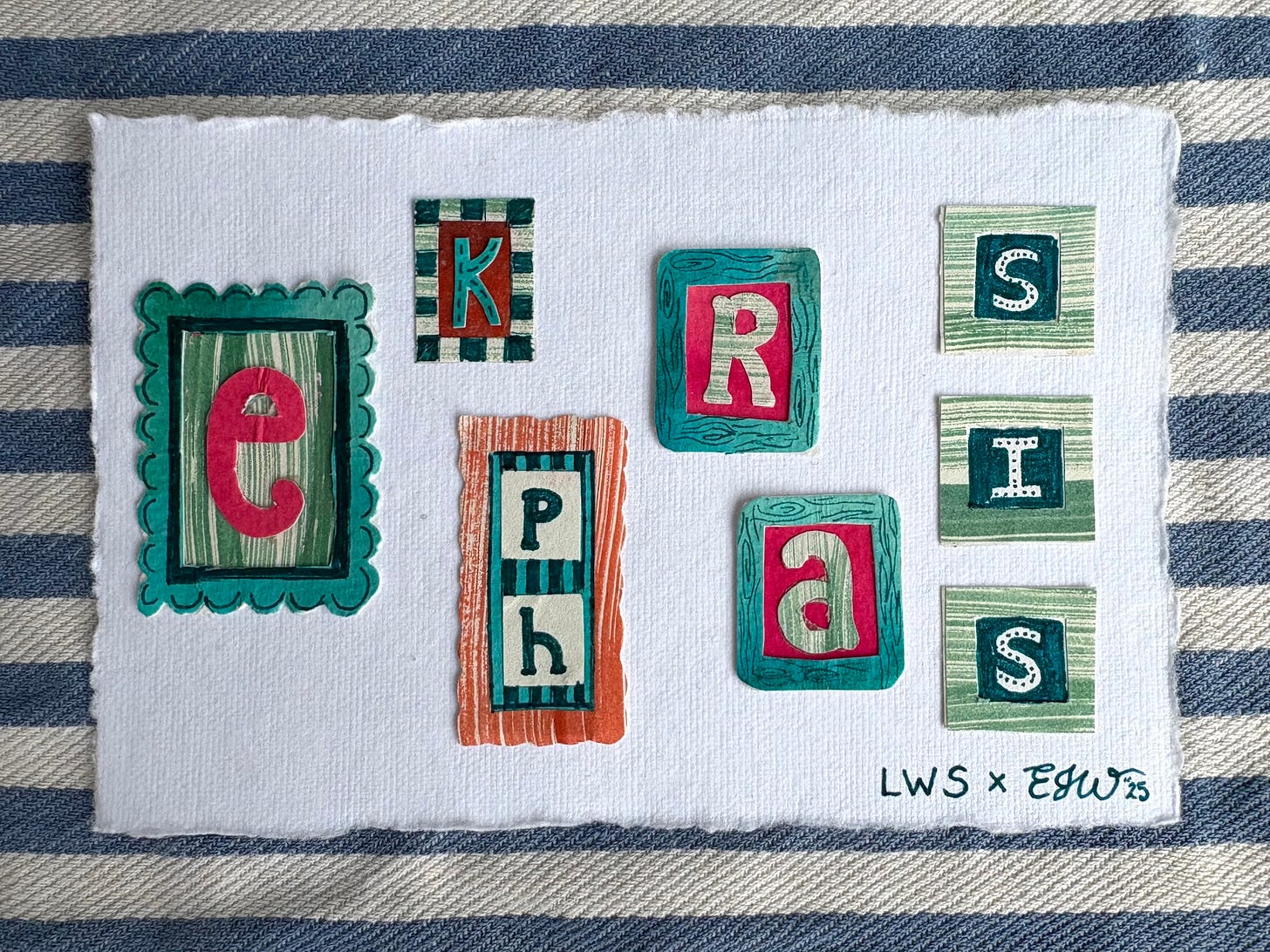

V. Ekphrasis

Inside Life-Size Drawing by Lai Chih-Sheng (2012) by Ella Leith

icarus and apollo spotted in small town of pine grove, mississippi by Elinor White

Skull, Immortalized: A Posthumous Accounting by Andrea Johnson

One More Night by Deepti Pinto Rosario [Readers’ Choice]

VI. Introduction to Creative Writing Cohort - Spring 2025

From Nothing & Nowhere (follow the Snake) by Louise Taylor

How to Travel Alone by Elizabeth Berman

Fire Opals by Fabiana Winter

Scribbles by Angela Allen

for when you can’t sleep by Judy Wessels

I. A Summer Memory

A Dark Green

by

are you

curbita pepo?

the name I save for the daughter I’ll never have and thus myself from future heartache;

the hushed chant in the room before a candle. And If I had a voodoo doll, I’d poke it;

the blocky print on a box, staring at me before I dump its contents into a glass of water for my heartburn.

are you

courgette?

a name my great grandmother heard in her village among the mango groves;

a tufting technique for handmade rugs;

the sound of a battery powered boat puttering across the water before it skips the bubbles and speeds off.

if not, then you must be,

squash

the game my best friend loves, but I always found posh;

the sounds my hands make foaming up a sponge with a fragrant soap before a bath;

the vines that the Piscataway tribe were surrounded by as they told us their myths and histories and danced for the rain to come.

how can you tell me that you are not,

gourd?

a hollow warm cave where my thoughts go to rest;

the babble a baby makes as its eyes glisten with excitement;

the touch of the earth with one’s bare palm and not stifling at the sensation of it moving slowly underneath.

how I wish you were,

how I wish you were.

but you are not.

Zucchini you are.

hot and blistering summer days with my father, his shouts booming for me to “hurry up” as I struggle to hand over the seeds with care;

I look past you in the supermarket dreaming of berries, walnuts and chard;

you are flushed with the color of fertility but I never tasted something so barren.

It is you I find in my dreams amongst the prickly ivy and dried rose bushes from years past.

It is you I find where you shouldn’t be, pressed up against the gates, where I only imagine stinking litter on the other side; skies of gray, the air bristling the hairs on my arms.

You are misshapen and grotesque.

Am I seeing the fruit with the magical names?

It sticks straight out of the ground by the stem. If there was sun it would be kissed. Instead, it hangs in the air bulbous and proud, as if it whispers “try me.”

My bare feet are pricked by the ivy’s sharp edges but I must retrieve this flower’s child before its wish is granted to a different stranger.

And I do, only to wish I had never dreamed of anything else as I hold you in my hands.

You are perfect.

No other name could matter as much.

About Nica Máre

Nica Máre is an academic/creative writer based in Berlin They’ve had academic texts published in books such as the forthcoming Forms of Migration Vol 2: Global Perspectives on Im/migrant Art and Literature. Their first published creative piece was the flash-memoir Arab Nights: An Intimate Recollection on Drag, Identity and Islamaphobia.Their writing is characterized as cosmic and ancient, referencing myths and the prose of the Bible to spark their audiences interest in social justice topics.

This piece was written in response to the prompt A Summer Memory.

Dead-Man's Float

by Patricia McTiernan

Rose of Sharon bushes grew along the fence behind our pool, an above-ground variety that occupied the southwest corner of my childhood backyard.

Sometimes, on hot summer days, my mother came home from her job at the bank, put on her black one-piece, and joined us for a swim. For her, the water was only a little more than waist deep, and she glided from one side to the other with just a couple of graceful strokes. Still, we admired her form, the way she confidently pulled herself forward, kicking her legs and windmilling her arms high in the air until one of her hands hit the far side.

She told us more than once that she learned to swim from the lifeguards at Fire Island.

“Do the dead-man’s float,” we asked, and she obliged.

I sat atop the pool ladder watching as she planted herself face down in the water, arms spread wide. I wonder now if that was an escape for her, that brief respite from our needy little lives. Did she hold her breath for thirty seconds? Sixty? Or maybe more than a minute. So convincing was she that I got a knot in my stomach waiting for her to return to the living. When at last she needed to breathe, she stood and gave her head a quick jerk, water flinging at us as her short dark hair was swept from her forehead.

I thought it was a gimmick, something she did to amuse us kids. But the lifeguards had taught her that, too. I just don’t remember her telling us it is a survival technique, a way for exhausted swimmers to hang on until help arrives.

About Patricia McTiernan

Patricia McTiernan lives in the Greater Boston, MA, area. Her personal essays have appeared in The Boston Globe, The Examined Life Journal, The Sun (Readers Write), and elsewhere.

This piece was written in response to the prompt A Summer Memory.

Which one of you geniuses

by Matthijs Schut

are we there yet?

it sounds

over a radio divorce

a fuller head of hair

leans against a warm window

it used to be warm

not this warm

I used to not wonder

whether my beach towel is sexy

or how many more summers

I get to summer

before none of this summer

remains

this car is rolling

so unhurried through the countryside

it must be standing still

then, all at once,

summer is here

the same dreams awake me

air keeps getting thinner

and I ask, once more,

which one of you geniuses

thought it a good idea

to give the future a gun

my back aching from the heat

is lifted off a sweaty mattress

I look around, to check

are we there yet?

About Matthijs Schut

Matthijs is an ecology student during the day, in cinemas at night, and noting down beauty in all the little moments in between.

This piece was written in response to the prompt A Summer Memory.

II. Conversation With a Place

Scattering ashes in the company of dragonflies and deer

by Kay Kroger

The ghost of my father’s fishing line whizzes past my right ear, way too close.

The Chippewa Flowage says there are walleye.

When I was twelve, I was the Pike Princess. My father would take them off the hook for me and wipe fish blood on his cargo shorts.

I ask the Chippewa Flowage if it remembers him. It responds slowly.

I am at the prow of an aluminum shoebox of a boat, water sloshing against the sides. I stare at a shoreline of thrumming aspens and pines.

An invasive species of carp floats by, bloated and belly-up. It does not remember my father.

Two red-eyed loons call from opposite places (aaaaaauuuOOOOOOO). They say yes, we remember him.

Over there, that’s the spot where I got my favorite jitterbug lure caught in a bush. My father took me back the next day to cut it out. The lure was green and painted to resemble a frog.

The Chippewa Flowage seems to ask if it needs to remember this white guy at all.

The air smells like marsh and woods, and the good kind of wet rot.

A black bear swims from one island to the other. The air is sweet and hot with the summer solstice, so I take a risk. I say

I think he belonged here a little bit. He belonged here every summer of my childhood, on the longest day of the year.

The Flowage says my father has gone off to live in the sun. I leave some of his ashes in the water.

I will visit him next summer on a June morning, at daybreak.

About Kay Kroger

Kay “Kro” Kroger (@kroetry) is a full-time on-demand typewriter poet. Kro teaches creative (type)writing classes and is poet-in-residence at the WNDR Museum. They have an MA in linguistics (2016) and an MFA in creative writing (2025). Kro’s debut poetry chapbook, Tales From the Abandoned Greenhouse (2024), was published by Bottlecap Press. Their poetry, essays, and creative nonfiction have appeared in Outpatient Press, The Prairie Light Review, The Thomasonian, Crook & Folly, and more.

This piece was written in response to the prompt Conversation With a Place.

To Barnaul, with Love

by Mauri Johnson

It’s been nearly ten years, but I know I could still walk your Siberian streets blindfolded. Even now, across the globe in my small town in America, I can still see the billboard outside our apartment on Popova street (“One dozen roses for just two hundred rubles!”) or the small, azure dairy shop by the bus stop. I can still hear the clattering of the tramvai rumbling along its tracks and the chatter of babushkas gossiping on their benches. I can still smell the combined aroma of cigarette smoke and sweat, shawarma and wildflowers, pirozhki and poppyseed.

Though I must admit, at first, I hated your concrete apartments in different shades of grey, the broken streets, the chaos of cars and marshrutkas, the disease of Maria Ra grocery stores on every corner—dingey and small and filled with produce too ripe to eat.

It wasn’t until your sunsets: bubble gum pink and lavender spread out over your concrete rooftops. And then, it was the white-winged butterflies and lilac bushes. And then, the wildflowers sprouting beneath green trees through cracked asphalt.

And then, you watched me starve myself for the first time—gorging myself on only fresh peaches and melon and pears—and sent me springtime thunderstorms and 3 am sunrises to bring me back to my body, the slow beat of my heart. You held me in the comfort of your candyfloss sunsets after a stranger on the street placed his hand on my breast and squeezed—just for the hell of it—and you caught my tears with your own clouds when I blamed myself. You cared for me as I learned what it meant when you are forced to grow up.

Often, I call out to you in dream-filled sleep. I ask if there are still tulips outside the first orthodox church I visited, if the woman still sells artwork outside the Aptek grocery store, if there are still carts that sell corn on the cob and giant metal kegs of kovac doling out small cups to children for the price of seven rubles (slightly more than an American penny). I ask if the mosquitoes still swarm like a biblical plague, if the summers still flush with life from the winter snow, if the people I gave my heart to are okay. I ask if you would recognize me now: still starving herself, but not as frequently; still ashamed, but less intensely; still herself, but so different. I have seen life and it has changed me. I ask if you would still want me. I ask if you ever miss me.

You always whisper back, Yes.

I think perhaps you spare my heart what it does not want to know. But I will visit again soon in slumber, where everything stands still, and it is always a Siberian summer, and neither of us has changed, and the world feels simple.

About Mauri Johnson

Mauri Pollard Johnson is an essayist, writing teacher, and amateur poet. She earned her MFA degree in Utah where she lives with her husband. Her work has appeared in The Normal School, Silk Road Review, under the gum tree, Punctuate, and others. You can find links to her work at linktr.ee/mauripollardjohnson

This piece was written in response to the prompt Conversation With a Place.

An Imaginary Conversation!

by Rathin Bhattacharjee

[Having grown up in a house with twenty four rooms, two courtyards, two railinged gardens, a rooftop that used to let us have a glimpse of the Howrah Bridge, and four doors including the gigantic ones used as the main entrance of the house in the heart of the city, I have lots of favourite places - one such being the thakurghar (altar room) with the chandimandap, the corridor with the curved pillars enclosing the area. I sweep the chandimandap twice a day, in the wee hours of the morning and in the late afternoon. On days, when I am troubled, feel let down, when my heart is filled with sheer delight and bliss, I keep talking to this place, to the thakurghar in particular. And I have this inexplicable feeling that all is going to be well with the world!]

Let me reproduce one such conversation. I climb up the two long steps in front of the takurghar, put my head against the central doors and pray silently.

An Imaginary Conversation Between The Thakurghar and Me ?

Me : I feel guilty I missed my afternoon sweeping yesterday. I was filled with some dread for the rest of the afternoon for that.

Thakurghar : I missed you. There aren’t many in the house who care for me like the way you do.

Me : I do it because I’m a coward at heart. Every single day I miss my duties, I’ve a premonition of sorts, like something terrible is about to happen.

Thakurghar : You’ve to understand that God isn’t vengeful. He doesn’t treat you based on how you treat Him.

Me : You know just a while ago, I asked this question to myself – What happens once the last of my siblings is gone? Will The Pujas still take place at my ancestral home?

(The thakurghar keeps silent and prefers not to answer my question thereby making me even more apprehensive.)

I was happy that Pupling (my daughter, Akanksha), having paid her contribution, could think beyond to purchase a benarasi sari for Ma Durga.

Thakurghar : She promised to buy Ma Durga a benarasi sari last year. I’m happy she’s kept her promise.

Me : That’s what I’m worried of now. Ten years from now, will she be able to do her bit for The Pujas?

Thakurghar : Have you forgotten the words of your late Ma? ‘So long as Ma Durga wants to come to your ancestral home, She will arrange Her own Pujas’.

That hopeful message from the Thakurghar ends our talk but keeps me brooding. The Pujas have been going on at our ancestral home for the last 65 years. Despite the divisions, differences amongst the families of my siblings and our apparent negligence, Ma Durga has been graciouus enough to keep visiting 41, Deblane all these years! This singular, yearly occurrence goes to prove the forgiving, benevolent nature of the Goddess beyond the understanding of an ordinary person like me. Let Goddess Durga be praised.

About Rathin Bhattacharjee

Rathin Bhattacharjee from Kolkata, India, graduated from C.U. He joined Bhutan Civil Service as an English Teacher in 1990h. An HM's Gold Medal Awardee (2018), he has been published extensively. His novel on Webnovel.com has won critical acclaim. So, have 4 of his other books, all published by Zorbabooks. Post-superannuation, he spends his time writing, blogging, podcasting, critiquing, editing and translating. His personalised FB Profile link is : htpps://www.facebook.com/rathin.bhattacharjee.1

This piece was written in response to the prompt Conversation With a Place.

III. I Have to Tell You

An Unexpected Honesty

by Dorit d’Scarlett

I have to tell you.

But there’s no good way, no ribboned version. Just the words, sticky with breath, broken off mid-sentence because something primal is howling through your chest.

You were folding towels. That’s the bit that haunts me. The mundane backdrop of the worst thing. You didn’t hear the sirens at first, not really. They thread through this city like trams – expected, distant, for someone else. It was your neighbour who called. Signe from number 7.

‘There’s an ambulance outside. Down the street,’ she said, voice too calm. ‘I thought— I just thought you should know.’

And that’s when time slows, doesn’t it? When the words stop behaving. You said: But he’s in the courtyard. He was just there. With his cars.

The towel slips from your hands. You open the kitchen door. Run barefoot over the tile, past the shoe rack with its small blue wellies still wet from the park. You call his name. Not loud at first. As if you can reel him back gently, as if it’s just a game of hide and seek and he’s waiting behind the bins, giggling.

But the gate is open.

You’ve told him a hundred times, haven’t you? Not to unbolt it. Not to touch the latch. That it’s different out front. That cars don’t always see. But he’s three. And you were folding towels.

You hit the street just in time to see the back doors of the ambulance close. The neighbour’s voice again, somewhere behind you: They didn’t even knock. They just took him.

He wasn’t crying. He wasn’t moving.

You didn’t know his bones could look like that. You screamed once, short and sharp, like something wild inside you snapped its neck. And now there’s a silence in the flat that won’t leave. His cup is still on the windowsill. The one with the red fox. His cars are in the dirt, a crooked parade beneath the bench.

And I, God, I have to tell you.

There’s nothing left to keep warm.

About Dorit d’Scarlett

Dorit d’Scarlett is a CALD poet and writer ‘of a certain age’ whose short stories and award-winning poetry have featured in Rattle, Meniscus, Antler Velvet, and many other international literary journals. Her long-form fiction has been long-listed for multiple writing awards. Awarded ‘Artist in Residence’ in Provence, France, she can consequently be found sipping Ricard as she procrastinates over prose. Links to her published work can be found on her website: doritdscarlett.com

This piece was written in response to the prompt I Have To Tell You.

At his feet

by Farhad Desai

I have to tell you that I should have been the one guiding the guru's foot into his loafer. It should have been me, using my thumb like a shoehorn to make sure his heel slipped in without struggle. He should have been touching my head and giving me his blessings. Instead, there I was, humiliated before everyone, helping his wife, Samaria, put her shoes on, getting her non-guru-blessings, feeling her claw-like hand on my head.

It's all political. Who cooks for the guru? Who cleans for him? Who gets private audiences with him? Who puts his shoes on? We'd all like to be chosen, but it's only for those who are willing to play the game. And the gatekeeper of the game is Shivani.

You want to serve him dinner? Call Shivani with a crisis. Let her know how lost you are and how grateful you are for her counsel. Sit with her. Let her console you and channel the guru as you remain lost.

You want to help him with his shoes? Well, a bigger commitment is needed for that. In addition to calling her occasionally in crisis, you also need to praise her every day and remind her that you'd be lost without her. The trickiest part is knowing who to denounce and who to praise. It keeps changing. And I really thought I'd got it right.

If you were chosen to put on Samaria’s shoes, it meant that Shivani was sending you, and everyone present, a message. You were going in the wrong direction. Maybe trying too hard. Maybe praising the wrong people and denouncing the wrong people. I didn't know. No one knew, except for an older disciple named, Vivek.

What everyone is aware of is that the disciple with the smallest ego is given the privilege of helping the guru with his shoes, and in return, receive his blessings. But the disciple with the biggest ego is given the privilege of helping the guru's wife with her shoes, and receive her pleasant, but non-guru blessings.

Everyone watches. No one comments, but they all understand.

So there I was. So close. Right next to the guru. Close enough to reach over and help him. Instead, I was left to smile and accept Samaria’s blessings, while Vivek received the guru's. I'd been trying to be where Vivek was for months now. I'd attempted to move up in the community while avoiding his help. At this point, though, I realized that I needed to make a change in my strategy. It was time to learn from Vivek instead of fighting him. Many had tried. I intended on being the first to succeed.

About Farhad Desai

Farhad Desai is a writer, thinker, meditator, and instructor. He loves to tell and listen to stories.

This piece was written in response to the prompt I Have To Tell You.

The Aura of Our House

by Claudia Excaret Santos

I have to tell you: I had the aura of our house checked. After a few paid sessions, they sent an image of the scan result… it was a terrible yellow, one of utter rage. I know you'll say this is nonsense, but what I feel inhabiting this space with you is yellow like a dry, stinging, featherless bird, yellow like an icy golden needle, like a scream.

I knew the yellow was there, but what I wanted to see was a small blue flower with a yellow center, like those that grow abundantly in the French countryside. I knew some yellow would be there, but it covered everything.

I know that you’re a man who wants to fly as a bird, but I still feel like a small round ashtray. And if a bird sings to me and I sing back, it warbles in my ear and I warble back, it hurts me, and I bleed.

One day, you’ll be a light bird, delirious in the air. I’ll find you in a charming landscape. But I want to be even if simple and inanimate, something that belongs.

About Claudia Excaret Santos

Claudia Excaret Santos (@claudiaexcaret) is a mexican writer, translator, and content creator. She received the PECDA Colima 2024 grant. She is a Sophia-FILCO Young Writers 2025 finalist.She has been selected by the international Rio Grande Valley festival to have her poetry published in the printed anthology Boundless 2022, and Boundless 2024. She has also been part three years in a row of the International Women Festival Primavera bonita, in Mexico City.

This piece was written in response to the prompt I Have To Tell You.

IV. In the Orchard

three applegarths

by Philippa Francis

1

corrugated rounds

punctured Dad’s back lawn

cut out like scone dough

to circle spoked sticks

with snail-eaten tags

Egremont Russets

James Grieve and Cox

tall as sixth-formers

start of a new term

my pockets bulged

with green rounders balls

walking tongue afloat

on hopeful spit

down pimpled concrete

to solve the riddle

stars not seen before

I’d unsneck our gate

the latch’s snap matched

my horse-grade chomp

teeth defurred I’d spit

pale unripe pips

hit Asquith’s red-ribbed

cultivator ping

flick stalks at docks

2

someone’s orchard sold

first pang of clearance

set a palimpsest

slanted ranks of ghosts

crossing beeless grass

always my head turns

scans for cavities

stubble of tree guards

3.

school run I’d slow down

my boys chucked conks

at a roadworks sign

for the clunk of it

may its rust still feed

that pelted hedgerow

lobbed cores now offer

autumn lantern fruit

About Philippa R. Francis

Philippa R. Francis lives by the sea in Sussex, England, although she comes from Yorkshire. She mostly writes photopoems combining her own images and words. You can find these on Ko-fi. Her fascinations at the moment include folklore, the unkempt, and creative defiance.

This piece was written in response to the prompt In The Orchard.

Trace

by Sua Im

I watch you appear and disappear between the trees. Eyes downcast, headphones on. The other students combine, as if pulled by intermolecular forces, into pairs and triads and more. But you and I, like noble gases, remain solo travelers on this autumnal school trip through the apple orchard.

The others fill their wire buckets, tugging too harshly at branches that reluctantly give premature fruit.

They giggle and screech, their voices floating above the treetops, sending a murder of crows scattering.

Later, when I am alone, I will repeat their words, to know how they taste on my tongue, how the tone vibrates my throat.

I follow behind you, reaching for the same trees you do.

My fingers graze something slippery. I see a writhing larva emerge from a fruit’s oozing wound.

I scream, and you turn around. For a moment, we lock eyes. Talk to me. But you turn away as if stung, as if I’m catching. As if you’re not already outcast, as if recognition wouldn’t elevate us to banality.

Eventually, I make sense of your path. You are following her, the one girl – petite and with unruly red curls – in a group of boys with recently broadened shoulders and nascent facial hairs.

They draw to her like she’s a bright light and you, a lowly moth hovering in the periphery. I wonder, how ignoble am I then?

She holds up a hand and lines it up against the boys’, one by one. They delight in how her fingers barely extend past their palms.

You look down at yours.

She reaches for a crimson apple, on her tip toes. A boy grabs her waist and lifts her up so she can grasp it. A squeak escapes her lips as the fruit is plucked, and she falls into him.

She takes a bite, slurping. She spits and throws the apple onto the ground. They leave, heading for trees of another species.

You make your way down the aisle. You arrive at the tree, your eyes searching for the discarded fruit.

You turn it over in your hand, bring it up to your mouth, and take a bite. You slurp, spit, and toss the apple onto the ground.

I take your place. The reject sits like a blood-red boil emerging from the grass. Bits of soil and dried leaves are stuck to its exposed flesh. I see your bite marks and hers, the jagged points already starting to brown.

I pick away at the dirt and bring the apple to my mouth.

About Sua Im

Sua Im (she/her) is a grade school teacher living in Worcester, Massachusetts, USA. She has been published in Ricepaper Magazine and has work forthcoming in Five Minutes and The Louisville Review.

This piece was written in response to the prompt In The Orchard.

A Worthwhile Crop

by Sandra Stratan

There are no seasons to speak of in the upper plateaus. As our readers may recall from our ongoing series about the crust’s monotone geography, the weather conditions in this isolated area of the globe vary abruptly between dry spells and high winds, which along with the ash-ridden topsoil conspire to make this land most unsuitable for agriculture.

There is, however, a most curious sight that no visitor should ignore: nestled against the county’s second highest ashmount (and therefore sheltered against the prevailing blasts) lies a purely ornamental orchard that is guaranteed to both fascinate and horrify.

The landowner is a retired synthobiologist who has discovered a bizarre endemic species on his property and has saved it from extinction with the help of an ingenious mineral irrigation system. He has kindly agreed to take us on a tour and share his motivation for tending such an unsettling collection.

As we stroll along the neat rows, kicking up sulphur dust and enjoying the crisp aroma of bogfill bushes, we might, for one brief moment, imagine ourselves in an ordinary orchard, spying ripening fruit of edelberr, grapple, and leatch. But here, it is the fruit that are spying on us, whispering to themselves as we pass. We can therefore no longer ignore their unusual nature and must present them accordingly.

They vary in size and shape, but most are roughly round or oval. Each one has a pair of eyes (yes, two!) located symmetrically above a wedge-shaped protrusion in the vicinity of their center. A slanted gap directly beneath it appears to be the source of the incessant noise they make, but the orchardist has yet to identify a clear speech pattern.

“As they mature,” he explains, “their features droop and folds begin to develop in their skin. They resemble crinkled pages and their screeching grows hoarse, until one day, their stem severs and they drop dead to the ground. I have preserved specimens from the last crops, but nothing compares to beholding them while they yet live. Do they not seem familiar?”

We gather our courage and approach an overhanging bough. The fruit’s similarities to the depictions of the Ancients are indeed uncanny. The orchardist’s theory is that the nameless fruit bear the final echo this crust has held onto of that long-forgotten species.

“Disaster and marvel are said to have followed them in equal measure,” he continues, “but I am of the firm belief that, contained as they are to branches and stems as well as a limited lifespan, these modern-day renditions can pose no danger to their surroundings. On the contrary, I cherish the hope that they will fuel a new wave of research into our much-neglected history.”

And while we do agree in principle, we shudder to think about the implications.

For those with courage to spare, pictures are to be found on page 12.

About Sandra Stratan

Sandra is a fantasy writer from Bucharest, Romania. When she's not losing herself in spellbinding stories crafted by awesome writers, she's plotting out her own novels while trying to withstand the adorable antics of her ever-playful German shepherd.

This piece was written in response to the prompt In The Orchard.

V. Ekphrasis

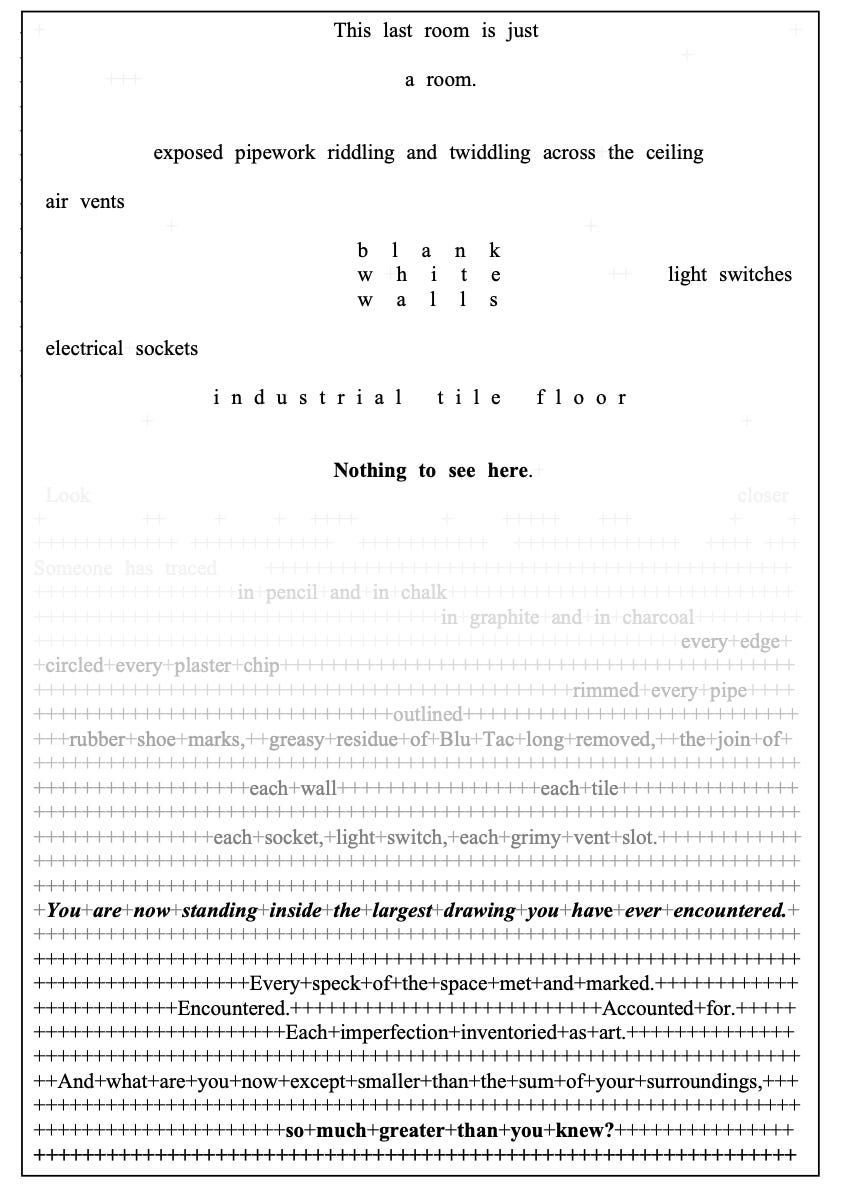

Inside Life-Size Drawing by Lai Chih-Sheng (2012)

by Ella Leith

About Ella Leith

Ella Leith (she/her) is a writer of fiction, creative nonfiction, and occasional poetry. With a background in folklore and oral history, her work usually explores how the past exists in the present, and how the weird and uncanny are found in the mundane. Originally from the Midlands of England, she lived in Edinburgh for sixteen years, and now lives on the Mediterranean island of Malta with her partner, a haunted terracotta bust, and several hundred notebooks. See www.ellaleith.com

This piece was written in response to the prompt Ekphrasis.

icarus and apollo spotted in small town of pine grove, mississippi

by Elinor White

; mama said the cicadas are always loudest when you aren’t listening to them. well if reincarnation is real then surely you’re icarus, the boy that fell for a god. the boy that flew so high, too high so that maybe for a second he could feel apollo’s lips against his. your mama always taught you to believe in god, but she didn’t know you’d find him in the warmth of another boy’s mouth. she doesn’t know that god laughs and tugs on your coat sleeves and kisses you again and sets fire to just about everything. and you sure ain’t listening to the cicadas now, ‘cause all you can hear is your pounding heartbeat and a couple thousand comets falling against the earth like his body on yours. mama, if love is a sin then this poem sure as hell ain’t a prayer for forgiveness.

About Elinor White

Elinor White is the pen name of a poet and playwright from a little suburb in the southeast where she lives with her family and two cats. When she isn't writing, she enjoys wandering around in places that she probably isn't supposed to be. You can find her on Substack with the handle @elinorwhitepoetry.

This piece was written in response to the prompt Ekphrasis.

Skull, Immortalized: A Posthumous Accounting

by Andrea Johnson

1479: Toledo, Spain

Beheaded during the Spanish Inquisition. Having been identified for neglecting three weeks of mass, my home was raided by hot headed Inquisitioners who were overly concerned by the presence of thirteen alchemy books and the absence of any holy books. They did miss my hymnal I had been using as a doorstop, but that’s neither here nor there.

1480: Toledo, Spain

Posthumously dug up by overly suspicious and far too superstitious local officials. Overflowing with intellect, they ruled me still dead. Surprise. Surprise. And tossed me out to sea.

1550: Island in the Cantabrian Sea

Found organically enshrined by seaweed in a cavern. A band of pirates who mistakenly thought themselves proper scallywags picked me up during their failed treasure hunt.

1559: Somewhere in the Atlantic

Less than amicably transferred into the possession of the Spanish Armada after said mediocre pirates were forcibly apprehended with a single cannon shot and a whole loot of incompetence.

1561: London, England

Traded by a drunken sailor to a local merchant for an ounce of tobacco. Not my most distinguished moment.

1570: Dover, England

Purchased by an ostentatious nobleman. After enjoying the praise of onlookers for nearly a decade, the man dripping in velvet and vainglory thought me a fitting relic to depict his well traveled worldliness. Dover being as far as his travels extended from his home in London.

1598: London, England

Donated by the nobleman's kin to The Globe Theater in desperation to maintain their family’s dwindling financial reputation after a substantial loss of fortune. I'll take theater prop to penniless pauper any day.

1599: London, England

Used as prop in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. I possessed an uncanny aptitude for dodging all audience shenanigans, maintaining my perfectly dignified profile every show.

1606: London, England

Snatched up by a Frenchman in the audience after being the sole surviving prop of a theater fire from an overly zealous torch scene. It was borderline theft. But I would’ve done the same. The firelight did wonders for my complexion.

1607: Bordeaux, France

Kept company with a chardonnay as old as I am in the Frenchman’s closet before being gifted to his painter friend. What a bore. Both the Frenchmen and the wine took themselves far too seriously.

1608: Paris, France

Perfectly posed in the painter’s study awaiting my debut. He constantly mused of death and mortality. Such Folly. Death has only brought me fame and enlightenment.

1609: Paris, France

Starred beside items of much lesser significance in the painter’s most inspired work.

1610: Paris, France

Smashed to pieces during a lovers quarrel after the painter's wife discovered his extracurriculars went beyond art and into the bedroom. So much for his moral and religious superiority complex.

2025: Le Mans, France

Immortalized in Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill. Less than thrilled to share the title with such a pretentious instrument. Nonetheless, I remain world renowned despite the academics’ preposterous take on my meaning.

About Andrea Johnson

Andrea Johnson is a Southern California native who planned to teach history after earning her degree from UCSD, but life took her in a different direction. She is now a full-time mom of three and spends most of her time caring for her family and advocating for her 10-year-old son, who lives with an ultra-rare genetic condition. She recently began writing fiction and has found it to be a growing passion as an interesting and creative outlet. Andrea writes on Substack at Reason and Fantasy.

This piece was written in response to the prompt Ekphrasis.

One More Night

by Deepti Pinto Rosario

I’d sell my soul

For one more night with you

In that café with the tables

That caught the moonlight

And threw it back up

Bathing us in pearly white

While stars bloomed like daisies

In fields of blue

I measure my life with the hours I spent with you

In that café, caressed with gold

Sipping coffee

Like we were immortal

To the ravages of time

To walk down that cobbled street, hand in hand

Foolishly counting our fortunes

Like lights that burned in the windows

That night

As the trees threw down sonnets

In rushed whispers

Like they knew

This night was the very last

That I would call you mine.

Inspired by – Café Terrace at Night, Vincent Van Gogh

This piece was written in response to the prompt Ekphrasis.

About Deepti Pinto Rosario

Deepti is a obstetrician who loves delivering babies. In her spare time she practices her other love - of writing. She enjoys spending time with her 7 children - 3 human, two dog and two cat.

This piece was written in response to the prompt Ekphrasis.

VI. ‘Intro to Creative Writing’ | Spring 2025 Cohort

From Nothing & Nowhere

(follow the Snake)

by Louise Taylor

Tricks, these before-creation soils.

The mind stutters, grasping for

contour, shape, form

to know

like a baby’s inquiring mouth.

But how can you hold the thought of

before-the-thought-is-thought?

1.

The medicine practitioner leading the meditation circle sings across the Zoom call, her tender voice accented by the shakapa, a leaf rattle–each shake, summoning the sounds of a cloudburst.

Ayahuasca... Medicina...

My body begins to loosen its grip on my place in the world: my mother's footsteps upstairs in the kitchen, scurrying about with preparations for the Christmas festivities, my aching head, a result of the previous night's once-a-year bonding ritual with my brother, the Colorado winter scraping at the window—all retreat from my awareness. I sink deeper into the mattress of the guest bedroom, held by the bed, held by the floor, held by the bones of the house, held by the earth. I let go of the external striving, the expectations, and sink through the layers of fatigue, the grievances, and into the soils of creation—cool, ancient yet churning, as if its movement is tilling time itself.

From the soil, the snake emerges, clad in warrior dress. She undulates from side to side, her scales glistening with diamonds and her eyes, two glimmering rubies.

We are paupers for words in the dominion of the divine.

The medicine practitioner, who had been guiding me through the wreckage of the last few months, sings the last verse of her icaros and gently invites us to bring our awareness back to the room. My eyes, soggy with tears, flutter open: wood panelling, my childhood quilt on the guest bed, branches laden with heavy snow that claw at the windows, framed by flat morning light. My feet prickle after having been crossed and immovable for the duration of the meditation. I cast about, searching for facts to moor my present circumstances: I was in my mother's house. It was Christmas Eve. And Grandmother Ayahuasca—Abuela—had just visited me with a very clear message:

I will hold you through the chaos. But, in exchange, you must learn to use your voice.

2.

My ask—to be stripped of the fallacies that had moulded my life—was rash. But things hadn't been going particularly well. I hadn't been able to sustain a satisfying romantic relationship in years, I was deeply mourning the absence of motherhood, and only a few months ago, the where I had worked for the past ten years had let me go in an organisation-wide financial crisis. "Tough times for us all," the HR manager said solemnly as she laid out the terms of my redundancy. And with that, the last of my dreams gave way to the heaviness of life.

The days that followed my dismissal unfolded with an unexpected, almost disappointing calm. I found myself longing for a dramatic consequence to match the pitched crescendo of my severance. But while friends and neighbours got up each morning to tend to the business of life, I was an actor who had simply made an exit stage left and no longer had a role in the play. I had been ejected from the frame of the story.

As the days stretched into weeks, my position in the wings offered me a privileged vantage from which to deconstruct the events that had led me here: the relationships that never took the edge off a gnawing loneliness, motherhood tipping from improbable to impossible, and the humanitarian missions—once a source of self-importance and adventure—had come to feel hollow and rote. That my performance had failed to reach its climax could be expected, and even explained. What was unexpected was the growing sense that after years of scrambling up the dramatic arc, the resolution promised by attaining romantic love and success was a bald-faced lie.

3.

At first, it was just a nagging feeling.

With no schedule to frame my days and nights, I'd wake in the unruly wee hours—the hours, according to my acupuncturist, when our spirits tended to fly around the room—deeply unsettled. Unable to find my way back to sleep, I'd fixate on the sliver of grey light seeping in from under the door. Logically, I knew that the only thing on the other side of the bedroom door was a pair of Havaianas discarded on the tile floor en route from the bathroom to the bedroom, but the sliver of light burrowed deeper into my brain like a thought-worm: I had to know. I stumbled through the darkness, fumbled for the door handle, and flung the door open. My cat sat patiently on my Havaianas, waiting to be fed. And the awareness flooded in: I had been chasing dreams that were never going to amount to happiness.

I slid down the wall beside the doorway onto the icy tile floor, struggling to reconcile my present situation with my newfound awareness, the air draping across my bare shoulders like a cold hug. The cat head-butted me, attempting to spur me into action, but I remained rooted to the floor, staring into the middle distance.

4.

I had been drawn to an international career by the idea of exploring the world. I imagined learning new languages, making friends from all corners of the world, and eventually my life would entwine with someone else’s in a tight braid. We would trade secrets while discovering the secrets of a new land; the place would be our story.

I imagined our flat together, marked by a transient lifestyle: a mattress on crates, framed posters leaning against whitewashed walls, a carefully curated bookshelf of treasures—but only those small enough to fit in a suitcase. We'd stay up too late drinking overpriced, bad wine and eating dinner on the floor, listening to song after song, our bodies luxuriating in the rhythms. Sometimes the music would call us to dance wildly, our feet beating like drumsticks against the floor. Sometimes it steered us to press our foreheads together, hands clasped to our chests, slowly swaying. And sometimes it would guide us to lie on the floor, starfished—my head on his stomach—just listening to the melodies floating above the din of the streets below. An entire life, perfectly lived between the four walls. We could be buried in that room.

One day, we would wrap the little treasures in bubble wrap and place them in a suitcase bound for a more permanent home: a stone house next to a lemon grove, perhaps, under which stood a long table. Our friends would join us there on holidays, we'd trade stories from the old days late into the evening, our laughter melodiously weaving with the tink and cling of dessert dishes and cicadas. The child would crawl into my lap, sleepy after zealously foraging in the kitchen garden with the other children, nuzzling her raspberry-stained cheeks into my chest.

Foolish girl.

Romantic love had been dangled in front of me like a prize, a means of accessing a fuller, more expansive sense of womanhood. But that special person did not come. I would try again and again—this time it will be different, I'd tell myself—but I was never able to reconcile the desire for love with the emptiness of the experience. As my childbearing years dwindled away, I would contort myself to find ways to defend and excuse the behaviour of the men I encountered, but deep down, I was offering up my own complicity to protect myself from the truth: there would never be a reconciliation. I had always been a thing to be consumed.

5.

I was stationed in Kenya when the word came of a colleague who threw herself off the balcony in Mexico. The news of her death spread among staff like pain radiating from a sharp jab to the gut. Why did she do it? Further details surrounding her death were quickly quashed out of respect for the family in their time of grief. And staff morale, some whispered. They wouldn't want us to get any ideas after all.

Because the truth was, a version of her story was in us all.

Every few years, the humanitarian missions would take me to a new place and a new life. But the chromatic experience of discovering the world slowly ceded to a niggly darkness—a darkness fed by loneliness and a sense of inconsequentiality to a life lived on repeat. But the fight for success and partnership seemed worth it for the life it promised: the comfort of moving through the world in the company of one's peers, along a well-trodden path that reassured me my time was well spent. Underpinning it all was the belief that one day, the external striving would lift me into an exalted state of living—a stone house beside a lemon grove, filled with treasures small enough to fit in a suitcase.

But there would be no child, no raspberry-stained cheeks nuzzling against my chest. My last attempt at realising this dream—IVF—fell apart when I acknowledged that I didn't have the necessary support to do it on my own. Or the courage. The thought of conceiving and giving birth – an act, in my mind, that should spring from a deep joy and love–as a single mother only rubbed the sense of loneliness raw. I bobbed and weaved in front of the decision, trying to muster the resolve to take the final step until age finally won its slow and steady battle, claiming my fertility.

I leaned against the edge of the balcony of my Nairobi apartment, staring at the parking lot's puzzle of grey bricks illuminated by the flood lights perched on the wall of the compound. Afrobeats played at low volume from the guard house, punctuated by chit-chat and laughter. The night looming beyond the floodlights felt uncontained and beckoning. A coaxing breeze nudged at my feet. What had been running through her mind the seconds before she—I didn’t even know her name, poor thing—jumped?

The grief churned and bubbled, menacing to overflow. It is such a luxury to let go, to give in to the thrall and let it carry you away.

6.

I was on sick leave for three months. When the psychiatrist deemed that I was well enough to return to work—remaining on sick leave can be counterproductive to well-being, he explained thoughtfully—I flew back to Nairobi. I didn't tell him the truth that the rest had only temporarily tamed the ravening head of grief. Like a patient living with cancer in remission, I was now living with death—at any moment it could claw its way to the surface and pull me under.

Once I returned to work, I could no longer do what they asked of me—to care. It came as no surprise, then, that I was discarded like excess baggage on the side of the road in the organisation's fight for financial solvency. But by then, it didn’t matter to me. The years of devoting my energy to sustaining the organisation's mission above all had cost me time and had eroded my identity until I wasn't even sure who was asking to be loved.

7.

I pressed the back of my head into the wall and shut my eyes. There it was, finally, the nagging thought-worm in full display: I had been pursuing love where it would not be found. Striving for professional success, chasing romantic ideals that I had been taught to want, had found me performing a version of myself that was driving me toward my own erasure.

I slowly got up from the floor and made my way to the kitchen. The cat moved to and fro between my legs in anticipation of breakfast. I opened a can of wet food and spooned out half into her bowl and shuffled onto the balcony. The December air offered no quarter. Still reeling from my realisation, I placed my hands on the metal balustrade to steady myself. The light from a distant streetlamp outlined the stone tiles on the terrace two stories below, beyond which loomed the inky black garden—a sea of tendrils ready to wrap around my ankles and pull me under. I shut my eyes: Let this darkness be your light.

In great, racking cries the grief poured out of me, tracing the contours of my daughter who would not be. The absence of her little toes, of her nose, of her curious eyes. I could almost make her out playing in the garden below, playing hide and seek among the feather grass and yew.

There was so much love on the cusp of death.

I inhaled the sharp air and, calling out to no one, to anyone, to everyone, invited chaos to destroy all the illusions that had governed my life.

About Louise Taylor

With 15 years of experience in the humanitarian sector, Louise's work has taken her far from her roots in Montana to Canada, Kenya, Lebanon, India, Haiti, and Thailand. She now lives in a French village outside Geneva, Switzerland, with her three-legged cat, Chloé, who she adopted in Beirut.

This piece was written as part of our Spring 2025 Intro to Creative Writing class.

How to Travel Alone

by Elizabeth Berman

He is on the train alone, watching the countryside pass. He feels the train increasing speed and sees a ravine ahead. Trees, flowers, wild grasses set the stage for a boy’s daydream on either side of the ravine. Jostled from his reverie, alarm overwhelms him. The ravine has no bridge. The train barrels forward. As he screams for help no one hears him. His body is tossed and the sensation of gravity pulls him through the air.

The boy startles awake, breathing heavily with beads of sweat on his forehead, relieved for the moment.

A thick early morning, the young boy studies the hazy rays of light streaming through dusty curtains.

His mind turns to the day ahead. He fidgets with Peter’s ear, his reliable stuffed rabbit. Biting the inside of his lip, a state of anticipation – an imbalance of relief, excitement and nervousness -- envelops his consciousness.

Peter. Baseball cards, marbles, comic books, string, toothbrush. I can’t wait to spend the night with Uncle Frank. Dad will pick me up. Mom says I will be gone for 73 whole days, as many days as today ‘til August! All summer, no shoes and no fire ants. I will miss Bill’s cooking and fishing. I will miss Mom…I wonder if she will write me letters, like she said. She went to bed so mad.

The disquiet and unknown unsettle his appetite.

Today, he escapes on an Amtrak train. He will travel alone. The train will take him North, away from the weight and heat of the Florida summer, fire ants, and his mother’s unpredictability.

A summer away promises to rejuvenate his child spirit and hope. His innocence is tarnished after a year of imbalance -- hope versus reality.

Every morning, hope sprouts evergreen with the possibility that today might be the day his mother becomes the mother of others - a mother who gives hugs, holds hands, says kind words, says “I love you.” Too often, the day’s reality transforms the boy’s hope into a fantasy.

His stepfather cooks breakfast in the kitchen, the smell of bacon wafts through his room. He hears his mother enter the kitchen. He hears her voice and knows. The scent of bacon blends with the scent of a freshly lit cigarette. He knows that his mother’s “night before” requires him to tread carefully. Her mood on mornings like this swings dramatically from light to dark – there is no twilight allowing for anticipation of the change. The boy will have to follow her lead.

All of this emotion and information is processed at the speed of the mind of a 10 year-old boy. And within minutes of first stirring, he bounds out of bed, dropping his beloved Peter on the packed suitcase. He buttons his favorite green plaid shirt. He heads down the hall to wash the remnants of sleep from his face and tame his hair.

In the kitchen, Bill balances his roles as stepfather and husband. He prepares pancakes and bacon for the boy, a hearty send off and distraction from the trip. Strong coffee and fresh juice wait for his wife. As she emerges from their bedroom, he feels her unstable energy. The morning heat, the stove and his wife generate a glaze of moisture across his forehead.

Bill is ordinarily handsome. Tall and strong, he wears khaki Dickies and a white tank top. High cheekbones, dark eyebrows and smile lines, frame kind eyes. He gets noticed around town.

He only loves her. She is like no one he knows. He can save her, he must save her. Early in their love story, he soared with her into states of being that pushed boundaries of imagination, and excitement, for a small town son of Tennessee. Perhaps, it was heaven. He did not know the word “mania.”

And yet these days, the price of “heaven passing through” is catching her, as she falls back to reality, and holding the rope, when she drops into her abyss.

Hearing the boy stir upstairs, he knows the boy is a trigger. He engages all his “tricks” to neutralize the alcohol induced anxiety rage that frames her view of the mornings like this.

Honey, you look beautiful! I’ve squeezed fresh orange juice for you and there’s coffee on the table. What would you like for breakfast? …looks like a hot one today. Let’s go to the movies, after we drop Tommy at the train – White Heat is showing in town.

In spite of his efforts, too often that frame of rage contracts…closing in his wife’s consciousness with barely a change in demeanor, save a furrow of her brow or a stiffening of her shoulders. And without warning, the rage envelops her and makes victims of anyone in her presence.

As much as Bill may want to protect him, the boy stands as a special target. He is the unwanted son of her love lost.

Every day – even with a loving, steady, supportive new husband in her bed – the boy is in her home. And, on too many days, the weight of love lost crushes her primitive maternal instinct. It hollows her out. Sometimes, she can play the part of the mother and “loving” wife – moving through the motions she perceives will fool them both. But when she can’t, she retreats to the safety of black…the darkest black, best induced by clear liquid contained in a red labeled bottle.

Her mood this morning is a by-product of that black, the boy’s departure and all the mixed emotion it stirs – relief, sadness, regret, guilt and fantasies of “if only” and “what if”. The black only provided escape the night before. This morning brings the reality that still remains, tinged with the emotion from the night before, an innocent boy, a loving new husband, an intense headache and the suffocating heat.

Cigarette between her fingers, she rests her head in porcelain hands as she sits at the red Formica kitchen table, elbows framing its white stripe. “Million Dollar Red” nails peek through her tousled curls, as she hides the dark shadows beneath her eyes. Her faded pastel floral robe hints at her past, where the “if only’s” began. Silk, lace, and exotic flowers print clash with the evidence of her now ordinary life, the Formica, the doting husband and her son.

Good Morning, Mommy!

An aura of evergreen envelops the boy’s greeting. He bounds down the stairs, his face lit with bright eyes, a smile and eager anticipation of bacon. He takes the last two stairs in one leap.

She looks up at the beautiful child and rests her head again in an attempt to keep the pounding from splitting it apart. The morning Camel cigarette is failing her. Its unfiltered nicotine elixir strains to contain her trembling hands, her racing heart and the relentless anxiety, churning deep in her psyche. Feeling his arms around her shoulders, she responds.

Good Morning, Love.

The boy continues…with paced excitement mirroring his inner thrill and fear about his trip. After a passing hug for his mother, he tips the chair as he slides into it and up to the table. Picking up his fork, he taps it mindlessly on the table, thumb and index finger serving as fulcrum…Tine, handle, tine, handle, tine, handle, tink, tink, tink, tink….

Hi Bill! You made pancakes! I love pancakes! Peter is on my suitcase. When do we leave for the train? How long will the train to Maryland take? What states will I go through to get there? Do you think I will see a baseball player on the train? Can you make me a peanut butter sandwich for the train? Thanks for the pancakes, Bill. When Dad picks me up I hope we go straight to the ice cream shop and then over to the junkyard to see Frank. Frank is so fun…he and dad make me laugh so much. Mommy, will you go with me to the train?

The sound of the boy's energy accelerates her churn. She takes another drag on the Camel, her head returns to her hands. She exhales.

Do not slap the fork out his hand. Do not slap the fork out of his hand. This is what he’ll remember. Hold your tongue…you know it will betray you…don’t say what you think. A good mother would make him breakfast. A good mother would hug him and feign excitement for his summer. But why should I care, I can’t care…he is my mistake. He’s in my space all year long, needing, and always wanting my love. But he won’t shut up about his trip. I’m exhausted…what is wrong with me…I want him to leave. I should feel love for him…but I can’t…I have none left to give. I gave it all to his father. Don’t slap the fork out his hand.

Bill, observing the stiffening of his wife’s shoulders and the clenching of her head, moves the morning forward.

Tommy, eat your breakfast. We’ll be leaving for the station shortly. I’ll make your sandwich before we head out.

The boy pauses, a flush of nerves tingles through his body. He realizes what is happening. His hands go cold and he stares at his plate. His excitement blinded, his read of his mother. His mind races…

What was I thinking? I know better. Why can’t I stay quiet? I need to stay quiet…look at the plate. Eat my breakfast. But my stomach hurts, I know I’ve said something wrong. Oh no! She’s looking at me. Keep looking down…don’t say anything. Eat the pancakes. Don’t scrape the fork on the plate. Chew with my mouth closed. I don’t want to see the look on her face.

Lifting her head, she pushes her chair back and rises from the table – silently. Cigarette in hand, she makes her way to the fridge and grabs the bottle on top – with the red label and filled with the clear liquid. She unscrews the cap, takes a swig. She turns and shuffles back to her bedroom. The door slams. They hear her weeping down the hall. She will miss the movie. She will miss the trip to the train station.

Bill sighs, unsurprised. He’s been holding the rope taught for the last few days, as she falls into her darkness in anticipation of today. He unties his apron, looks at Tommy with his sad, kind eyes.

Tommy, go get Peter and your suitcase. It’s time to head out.

His kind tone and warm hand on the boy's shoulder salve the wounded hope enough to keep tears at bay.

The boy heads upstairs to get his suitcase. His mind returns to the day’s train trip. Almost to the stairs, he turns back to grab his baseball cards, marbles, comic books, and a baseball, shoving them into the bag. He’s forgotten the string but the train won’t wait.

He tastes the pancakes in the back of his throat. Suitcase in his right hand, he gives Peter a squeeze that allows him to start his journey – down the stairs, through the kitchen door, into the car and onto the station.

About Elizabeth Berman

Elizabeth Berman grew up in a small town in Southern Illinois. She worked her way up through Democratic politics over the course of a decade, travelling and meeting people all over the country. She capped her political career in the Clinton White House.

While at Catholic University, she received a “masters degree” in political common sense working for political adviser James Carville and learned the importance of the love and labor people bring to the world.

“Retiring” to New York, she worked as a public relations counselor. And then, raised three city kids with the help of her adoring husband and the NYC Public Schools.

She loves the art of observation, listening and laughter, as well as engagement of people and natural beauty. Currently on a renewed quest of self-discovery, she aspires to use writing to help process past experiences and elevate observations, ideas and hope.

This piece was written as part of our Spring 2025 Intro to Creative Writing class.

Fire Opals

by Fabiana Winter

Vóltoc, the Realm of Fire, after midnight. Far out in the Rubín Sea, Anileís, the most relentless of all volcanoes in the realm, possessed an entire island, its lava flowing in branching rivers over volcanic terrain. The volcano’s heart quivered in an arena of thousands, all ravenous for the island’s legendary spectacle: fire-wielding warriors burning each other to the bone – unless Anileís devoured them first.

Most spectators were Huvocai, human-shaped creatures clad in volcanic rock. Others hid their true nature under hooded cloaks and masks of fake volcanic rock, like two royal daughters in the front row who had just come of age: Sephone who was herself from the Realm of Fire, and Zora from Äithéra, the Realm of Air.

“You’re insane!” Zora hardly heard her own voice between barbarian roars, could hardly breathe in the stifling air of sulphur and rotten flesh. She prayed she wouldn’t be the next one to be scorched by another lava splash spewed up by Anileís from the arena’s fighting ring.

Sephone’s crimson eyes blazed against the anthracite mask. “Shut up and enjoy the show.”

Blood boiling, Zora turned to the ring. Like most spectators, the two warriors were Huvocai, too, their skin a volcanic shell. Zora knew they could look just as human as Sephone and her. They had to trigger their shell consciously; only then were they immune to foreign fire and lava. The warriors rode Anileís lava waves on swimming islets, hurling streams of flames at each other. Zora knew that the mighty Huvocai controlled even lava. Gods. How the hade could Sephone do this to her? Her friend drew no lines when it came to adventure, but Zora had always thought she would draw one for her. Apart from the fact that they could both die, if Zora’s folk, the Néra, ever learned that she was here, among their natural enemy…she didn’t want to think about it. The Néra were the proudest and most ethereal creatures in the entire kingdom of Ónerion: born in the skies, their wings pristine as a swan’s feathers, their skin glowing like sun-kissed silk.

Sephone cheered at the brawnier warrior. He threw whirls of fire that could burn down houses. It reminded Zora of the Huvocai’s history, and why the Néra detested them so much. The Huvocai had set entire villages on fire, had roasted innocent men and children, had hunted women like prey – in Äithéra more than anywhere else. Her Mama would say, “It’s in a monster’s nature to seize an angel.” Zora shoved away the thought, watching the two Huvocai with bated breath; how they played with fire, ducked and twisted at dizzying speed, never flinched when lava splashed around them. She found them fascinating, even intoxicating – that alone was treason in Äithéra. Although whispers circulated that the Huvocai had changed in the last decades, some even being welcomed into civilization, the Néra remained stubborn as stone. They still believed the Huvocai were monsters. Incapable of empathy, affection, let alone love.

The two Huvocai came closer and closer until, from an islet in the ring’s centre, the brawny swirled up a lava tornado, channelling it at the leaner warrior in the ring who hurtled from islet to islet until he slammed into the stone railing right in front of the girl’s seats. He dug his feet between the pillars of the railing and pushed the tornado back to the brawny, his volcanic shell splintering from his body, piece by piece. Sephone, like many others, applauded. Zora swallowed. A naked man, right in front of her. And the railing offered too little coverage.

A tug on Zora’s arm. Before she could even look, she was in the warrior’s grip, her thighs pressed against the railing. His eyes bore into hers, two fire opals born in the lava. His mahogany hair was dripping; his young skin was slick and feverish. Zora was melting beneath cloak and mask, her heart drumming in her whole body. Before she attempted to wriggle out of his hold, the warrior loosened his grip. Then he caressed her back – what was happening here?

He panted. “Please.” His deep voice sizzled beneath the arena’s roar. “Save my life.” His knuckles brushed her masked cheeks. “Kiss me.”

Kiss him? Zora bit her tongue. Was this a game to him?

“For the gods’ sake, kiss the warrior!” Sephone’s mask-muffled voice.

The warrior’s chest was heaving. “No, no games.” As if he’d heard Zora’s thoughts. “This is real.”

The honesty in his eyes and the rawness in his voice touched Zora’s heart deeper than they should have. She sorted her rumbling thoughts, her eyes falling onto his orange-glowing chest, his perfectly sculpted arms.

Lava exploded in the arena’s centre. The warrior twisted his head, and Zora’s gaze darted past his pretty profile to find his opponent, the brawny, breaking the lava’s surface – his volcanic shell was intact. Zora’s eyes trailed back to the bare arms holding her, and widened. Of course! The warrior was, in comparison with his opponent, naked, defenseless against fire and lava without his shell. Could her kiss…trigger it?

“Please,” the warrior said softly, waiting for Zora to decide over his life.

She couldn’t breathe, couldn’t think. The Néra would never see their princess in her again, and her Mama would never see her daughter. But if refusing the kiss meant the warrior’s death… She was thinking of baring her wings, flying him out. No, they would catch her the moment she tried. Her mind screamed at her to flee; her heart whispered for her to stay. And then she lost all control over her body, as if nature was pulling her towards him – fire craving for air to feed it.

“Forgive me, Mama.” Zora freed her mouth from the mask, laid her leather-gloved hand around the warrior’s neck. The warrior’s eyes fluttered shut until the last bit of tension around them dissolved and dark lashes rested above flushed cheeks. The sight of him devastated her. He ought to be repulsive, brutal, savage. He was none of those things. He was tender, affectionate, beautiful.

Zora closed her eyes and kissed him.

His lips tasted of sweet sweat and cardamom. His chest was a hot stone warming her covered breasts. If they were bare…she couldn’t help but moan. She had obviously lost her mind.

Zora felt a scratch on her cheek, heard a crackle. The warrior pushed her out of his grip. Zora gasped, catching herself on wobbly legs. She lifted her eyes, chest frantic, heart hopeful. The warrior transformed in seconds until the last bit of smooth skin was coated with volcanic rock. Yet his eyes were still…his.

Someone tore at Zora’s arm. “Let’s get out of here!” Sephone.

Zora looked past the Huvocai, the man she kissed. Anileís’ entire river raged, sweeping the arena. The Huvocai’s eyes softened. “Thank you.” Then he faced his opponent, and Anileís.

Zora’s heart ached. She didn’t even know his name.

When Zora and Sephone had reached their flying carriage, Zora realised the moment was over. A moment the world would never know. With the rise of the sun, she would have to live with the secret and the guilt of having betrayed her folk, her Mama. And Sephone would carry that secret with her. But as long as the moon graced the night sky, Zora listened to a song of her soul she would never forget. It was a song of longing and gratitude. Longing for fire opals and cardamom lips and heat and intimacy; gratitude for that she felt all these emotions, had fought for her own beliefs, had followed her heart.

And, after all, Zora had learnt two important lessons: even a monster could be beautiful, and even an angel could fall for a monster.

About Fabiana Winter

Fabiana is a writer based in Switzerland. Her current WIP is her debut Fantasy novel set in the world of this short story. She finds her greatest inspiration in nature, language, music, chocolate and intriguing personalities. Fire Opals is her first published piece - and she is quite thrilled about it. Find her on Instagram @fabisepics.

This piece was written as part of our Spring 2025 Intro to Creative Writing class.

Scribbles

by Angela Allen

Anne frowned and slapped her pencil down as Curtis breezed into the dining room, his phone conversation swamping her hushed solitude. He planted himself, laughing, at her right elbow and announced,

“Anne? Yeah, she’s sitting here, scribbling again.”

Anne snatched a thick black pen from his back pocket and dashed off a note:

“Off to ‘scribble!’ Sandwich in the fridge.”

Snapping up her carrot-colored notebook, she attached the pencil holder and strode to the front door, letting it bang behind her. Outside, she inhaled the scent of wild roses climbing without constraint and thought about that word: scribbling. Two dismissive syllables that propelled Anne’s strides to the end of the block.

A tickle of thick fur against her ankles and the rumbling tones of feline song: Emmaline. The three-legged gray cat gazed into Anne’s hazel eyes, listening as Anne told her:

“My character analysis! Curtis tore those pages out of my notebook while he was on the phone. Wrote phone numbers on them and left them wadded up in the trash!”

Emmaline blinked her emerald eyes and said “Mew-wet!”

“Exactly, Emmaline!” Anne told her furry confidante. “Unacceptable.”

The air shimmered with possibility and the scent of mystery. An arched entrance to the cemetery beckoned her, the wrought iron still gleaming with morning mist. She strode onto the grassy carpet of the memorial garden, her dark wavy hair swinging against her shoulders. All around her, lilac buds were ready to burst, bright white and vibrant purple gleaming beneath green leaf shells. As Anne picked her way through the headstones, she read some of the epitaphs to Emmaline. “Gone But Not Forgotten.” “Reunited At Last.” “Love Is Enough.”

“What would Curtis put on my headstone?” She asked. “Still scribbling?” Anne’s bark of self-mockery bubbled across the subdued space.

Her pathway led to a 100-year-old bronze memorial erected in memory of a spaniel. The simple inscription read: “Rex,” and across his paws lay a tumble of branches offered in tribute. Anne stroked the sculpted lines of the dog’s head and ears and watched as Emmaline leapt onto a stone bench nearby for a nap in the sunshine. Anne’s scalp prickled, and she glanced over her shoulder. Rex’s head was turned, his eyes gazing directly into hers! She paused, her mouth agape. Tiny scurrying feet stirred the nearby bushes, and a magnolia warbler called out its song of resilience– “weta, weta, WETA!” She blinked, and when she opened her eyes, the dog was back in his normal pose. As she resumed her steps toward the back gate, a single headstone, lopsided, caught her eye. Its original white surface was pitted and yellowed with age; the inscription obscured by a patch of weeds. A messy anomaly in these well-manicured grounds. Anne knelt, pulled the weeds to one side and read:

Phoebe Grant

1844-1879

Her finger traced the edges of an engraved quill and bottle of ink beneath the dates. A writer! Phoebe, goddess of intellect and prophecy. Anne yanked the weeds from the ground, then sat back on her heels. Thirty-five years old. What stories didn’t Phoebe get to write? Rising, she stepped to a nearby lilac bush, broke off three sprigs as a tribute, and lay them before the stone.

Outside the cemetery gate, a red metal toy pickup sat sideways on a tiny patch of ground: an invitation to play. Anne smiled as she knelt and trailed her fingers along the two-inch high wall surrounding a child’s garden. A place for imagination. She pushed one finger against a red wooden door set into the wall. What if she could stroll through it and sit at a table on the tiny patio just inside or climb into the treehouse nearby and have tea? A blue tea set beckoned, just visible through one of its windows. Anne’s fingers tingled–a place to write.

Two legs stuck out of a pile of dirt. Anne pulled him out–a small plastic man, molded dark hair, blue jeans, black t-shirt, and shades, a notebook clutched under one arm. She lifted him onto her palm, dusted him off, and lowered him onto the treehouse balcony. As she did, an object gleamed in the turf below him, and curious, she reached with one forefinger and thumb to grasp a tiny golden key. It glowed as she lay it on her palm.

Anne’s phone pinged, and she ignored the summons, her attention on the glowing key growing larger and heavier in her hand. She sighed as her phone pinged again, flashing a message:

“Curtis: Where are you?”

Her thumb hovered to answer automatically, but a voice called,

“Anne! Come inside!”

She lifted her chin to see a man--no, the man--waving to her from the balcony of the treehouse. A full-sized treehouse located just beyond the wall that was now shoulder height! She blinked, but the treehouse and the wall were still there. A wall with a red door and a keyhole the size of the key she held in her hand.

“Where am I?” She gasped.

“The Red Truck Garden,” he answered. His grin grew wider, and he pulled his shades lower on his nose. “Your place to write!”

“My place?” She stammered, wide-eyed.

He nodded as sounds came from beyond the wall: the chime of dishware, soft laughter, and voices. A glance at her phone silenced them. Anne lay it face down on the wall and stepped back. A breeze feathered her skin, the sounds resumed, and the key vibrated on her palm. The red door swung open with a groan.

He waited just inside and tucked her hand inside his arm.

“I’m Oliver,” he said, smiling as their eyes met.

She reached up to touch his nose. “You still have some dust—!” And she brushed it off, laughing.

Hours later, Curtis, his face thunderous, demanded,

“Where were you?”

“Scribbling!” The word sprang from her mouth.

“What?” he asked.

“Never mind.”

One year later, Anne published her first novel: The Red Truck Garden.

About Angela Allen

Angela Allen met some of the characters in “Scribbles” while she was on a walk with her youngest grandchild. Angela flung open the windows to imagination after 15 years of teaching academic writing and literature at a small, private university in Washington State. Before that, she was the business manager and co-owner of a small business with Steve, her partner of 53 years (who is nothing like Curtis). You might find her camping, hiking, or canoeing in the Pacific Northwest, or enjoying a glass of wine in Vernazza, Italy. She is currently finishing the first draft of her first novel, when she’s not distracted by short story ideas or sleepovers with her four other grandchildren. “Scribbles” is her first published piece of fiction.

This piece was written as part of our Spring 2025 Intro to Creative Writing class.

for when you can’t sleep.

by Judy Wessels

Should you find yourself

alone

in your skull, that cavernous echo chamber

in the dark

(what passes for the dark)

in the city

stifled and stuck in your overheated self.

Your body, an old woman’s body (a prison). Heavy.

And your thoughts, a young woman’s thoughts, sharp and stinging,

spinning here and then cutting there.

The sick green light of your phone catches

in your throat. Let me out. Let me rest in the escape that is sleep.

No.

It is too late.

It is too early.

And you can’t sleep.

Soon you must get up and go to work at

nothing meaningful, or

real. No thing.

You make nothing, you do nothing (you are)

And this awful nothingness of tomorrow is the blessed release you crave

now!

Dull. Exhausted.

Like the plant not watered while you were away on holiday, not sleeping, in your beach facing room.

The room you paid extra for to see the stars and smell the ocean but all you saw

was the flashing red of the smoke detector

and all you could smell was cedar wood and lemon and granny smith apples

Air freshener.

Dear one,

when you can’t sleep

the first thing to do

the best thing to do

the only thing to do

is

close your eyes.

About Judy Wessels

Judy Wessels is a writer from London via a small town in South Africa.

This piece was written as part of our Spring 2025 Intro to Creative Writing class.

Thanks for joining us for this special issue of Writers’ Hour Magazine.

Want to take part? Subscribe and you’ll receive our weekly contest prompt straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Honored to be among such great writers! 🥹